Tunisian Literatures

Tunisia has a diverse literature, but one which is often compartmentalised either under Arabic or Francophone literature. To counter this limited view, I have approached it in its linguistic multiplicity (Arabic, French, English and the Tunisian dialect) but also paid attention to its different modes and contexts over almost one century. This has resulted in research on the Tunisian poet Abu ‘l-Qasim al-Shabbi (1909-1933), who had a tremendous impact during his lifetime and continues to be Tunisian national poet, Mahmud al-Mas’adi, Francophone writers, the poet Awlad Ahmed, life writing, historical fiction and beyond. Here, I collect together various publications, lectures, discussions and thoughts about Tunisian literatures.

Mosque in Testour

Multilinguality in Tunisian literatures has roots and antecedents in Tunisian theatre, film, poetry and fiction. The literary movement known as the Avant-Guard, Al-tali’a al-adabiyya, which thrived between 1968 and 1972, sought to “revolutionize” literary language and to root literature into the multilingual environment and social reality of Tunisia on the backdrop of a Leftist turn in local dissident politics. It sought to complete the process of language and literary decolonisation. Fiction and poetry by Izzeddine al-Madani in drama, Salah al-Garmadi, Tahar Hammami and others defies dominant critical approaches and challenged translatability. Al-Tali’a and the tradition, which stretches from the 1920s to today, compels us to take into account the multilingual dimension as a fault line of its own, as confluency/tarafud, a form of confluence and interaction of languages within the same text. This tarafud necessitates a different way of reading, a multiple and multiplying critical practice, which I pursue in a forthcoming essay.

Since the issue of language usually arises when other social and political factors come to the fore, as Gramsci has argued, it should not surprise us that the language question in the context of the 2011 revolution was articulated in terms of democracy and social justice. My short piece, “Literature Unchained”, charts the emergence of increasingly diversified literary voices, unburdened by cultural taboos, linguistic norms and dominant figures and trends. A most notable tendency of writing has been an explosion of memory writing or testimonies. In the essay “Poetic Justice” (in French) I argue that, whilst this period of transitional justice, in which post-revolutionary Tunisian society reckons with its own past, is yet to end, and indeed may still lose its way, literature emerges as a site where such justice, in the sense of testifying to the authoritarian repression and holding them to account, has been and can be accomplished. I also have a forthcoming essay on law and literature, a summary of which can be found in this podcast.

Perspectives activists in prison

Much Tunisian literature of the post-colonial period has been concerned with developing and extending the national consciousness, imagining new futures and different ways of being. For example, the movement Perspectives was instrumental in reimagining the ways in which Tunisian society might be organised and therefore (re)presented in novels, plays and films. Despite their eventual demise, the group has long been central to Tunisian imaginations of protest, revolution and change; they were seen as pioneering figures in giving voice to the Bourguibist failure to transform the Tunisian people from subjects of a colonial state to free and empowered citizens. Their interventions into Tunisian culture have long remained the guiding principle of opposition to statist and authoritarian policies since.

Carthage

Much of my work on Tunisian literature has addressed the development of a national literature in the colonial, post-colonial and revolutionary periods from a broad-brush perspective, reading across texts, traditions and authors to approach big questions concerning national consciousness, thought and self-expression.

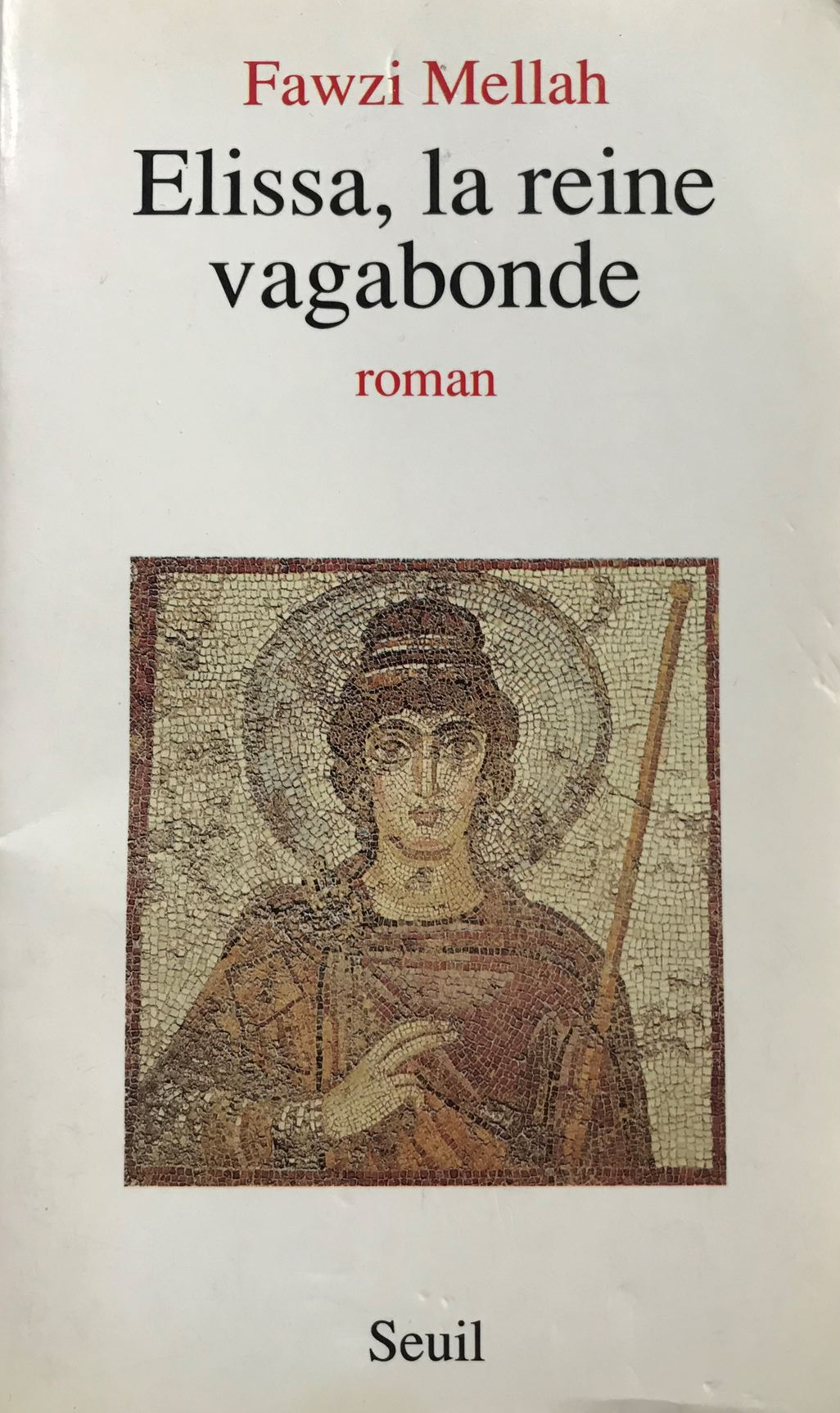

Memory and history both weigh heavily on Tunisian cultural production. Ancient Carthage, the Ottoman past and French colonialism have been subject to extensive narrative literature. Novels, plays and articles by Fawzi Mellah, who writes in French, display a ground-breaking engagement with the concept of memory and decolonisation of memory. In this article, I argue that Mellah’s works show a simultaneous questioning and reconstruction of memory as a form of communal and personal meaning in modern Tunisia. The past must be wrestled out of its hegemonic Roman and Western depiction of Carthage and its symbols. Likewise, his depiction of Tunis in particular appears to de-anchor it from time, severing the link between the concrete, the architectural and representational from that which it represents or commemorates.

The Ottoman period, another significant knot in Tunisia’s long history, has also been the subject of extensive treatment in literature. Bechir Khrayef emerged as pioneering figure in revisiting that period, with a view to respond to French claims on the territory. In an essay on historical fiction in modern Maghrebi literature, I argue that a period defined by the intense search for a nationalist historiography, a search for a historical identity around which new polities could coalesce, was important for the construction of a national consciousness. There has been such a marked interest in the immediately pre-colonial period of North African history before the emergence of European settler-colonialism.

Sidi Bou Saïd

Tunisian self-conception, the conception of the Tunisian landscape and space, was transformed by the twin development of an indigenous and a colonist narrative of Tunisian territory. I discuss these twin imaginings considerably in my article on settler-colonialism in Tunisia. Whilst our reading of colonialist literature can explore the development of alternative imaginations of Tunisia as a space and people, alternative conceptions of history, of Tunisia’s place in the wider world, we must reckon, ultimately, with this literature as the site in which power, the control of a real, extra-textual territory is being acted out. Tunisian colons, developing their own conception of Tunisia as settler-colonial space, inscribed into this land their own visions, dreams and self-conceptions. In this article, I compare such narratives with indigenous ones, interrogating how the two literatures affected, reflected and opposed each other.

These are the main broad areas I have explored in depth in my writing. However, in several occasional papers, I discuss other aspects of Tunisian literature and cultural production. The Tunisian novelist, literary critic and politician, Muhammad al-ʿArusi al-Mitwi, is the subject of an entry in the Encylopaedia of Islam (THREE), which you can read here. Al-Mitwi has hardly been studied at all in modern literary criticism, and, outside a few French anthologies, his work has never been translated, despite being taught at both primary and secondary schools in Tunisia. His major and most profound influence on Tunisian literary culture was his work as a publisher and editor, his enthusiasm for establishing institutions, spaces and magazines dedicated to fostering literary culture.

Tunisian literature in the 1990s marked a turn to more open writing with the changing of the generations, which I explore here. Interest by Tunisian writers in what we might call Europe’s Islamic past is also worthy of exploration in light of the country’s long and complicated Mediterranean history, but has not had sufficient attention, perhaps because a lot of it was written in French or in English. The work of Abdelwahab Meddeb was particularly important to me since it traces the intellectual linkages and reference of Arab and Muslim culture in Europe. Furthermore, the works of Sabiha al-Khemir raise the question of diasporic representation of Tunisian identity.

Whilst much of my academic work has concerned the broad-brush, intertextual, thematic and comparative approach discussed above, I have also worked extensively on specific authors. Below, there are sections devoted to Abu al-Qasim al-Shabbi and Awlad Ahmad, two Tunisian poets who have been formative in shaping the national literature.

My work on Mahmud al-Masʿadi is in a separate section of this website.

Abu ‘l-Qasim al-Shabbi (1909-1934)

Calligraphic representation of al-Shabbi’s poetry

Abu ‘l-Qasim al-Shabbi is a major world poet by any standard. His work captured the spirit of his times, a period marked by the emergence and proliferation of a revolutionary movement to shake off the colonialist domination, underdevelopment and repressive traditions, and achieve national liberation in Tunisia and across the Arab world. More recently, his poetry has been taken up by freedom fighters from Morocco to Yemen, with protestors and revolutionaries singing his songs, displaying his words on banners and in slogans. Some of his lyrics have even made their way into the post-colonial Tunisian national anthem. He became a national poet, and a major source of pride and display in his native town, Tozeur. My work on him covers his poetic legacy, as well as a research project on tourism and culture. I have written a long biography of the poet in Essays in Arabic Literary Biography 1850-1950 as well as a shorter reference entry in the Dictionary of African Biography. Parts of the tourism project, which takes him as central theme are exclusive to this site.

However, despite the global appeal of his poetry, his work stems from a particular poetic and literary context. Al-Shabbi, much like European Romanticists’ rejection of classicism, was radical in his critique of the traditional styles of Arabic poetry, moving away from the familiar structured methods of versification, towards a more fluid, novel style.

Bust of al-Shabbi outside Tozeur

Born in Tozeur in 1909, al-Shabbi was later educated in Tunis, studying at Qur’anic schools, al-Zaytunah University and the School of Law. Despite his studies, the death of his father and his marriage, al-Shabbi refused to get a job, claiming instead that he needed freedom to spread his poetic wings. Whilst al-Shabbi’s influence on modern Arabic poetry is profound, as was his ability to bridge the cultural gap that existed in the period between the Arab East and West, his untimely death at the age of only twenty-five cut short a promising life. However, there is a small cottage industry related to al-Shabbi’s life and poetry which far outweighs his own poetry and prose - there are more poems written about al-Shabbi (over 140) than by him!

Al-Shabbi’s poetic style, his rejection of tradition, did not simultaneously mean a rejection of the Arabic language. Rather, he was deeply committed to reading and thinking about classical Arabic literature and poetry, in particular entering into the thorny debate over al-khayal (imagination) in Arabic literature. Noting in his article “Poetic Imagination Among the Arabs” that myth was rare among pre-Islamic Arabs, he compared early Arabic culture unfavourably with Greek and even Assyrian cultures; like many of his contemporaries, al-Shabbi’s comparisons stem from the desire to understand the modern Arabic relationship with Europe through an investigation of Arabic pasts. One of al-Shabbi’s most insistent views on Arabic literature was that one ought to know the past, but that the past cannot be used to answer present-day problems. His work has often been called an attack on tradition and understood as a shallow and immature misrepresentation of the history of Arabic poetry and literature. His “Poetic Imagination…” was rather an attempt to mount a vigorous rebellion against a stagnant art form and culture. It was an intellectual struggle, which he shared with his contemporaries in literary and intellectual circles of the late 1920s and early 30s. Many of these ideas were also found in his al-Shabbi’s poetry.

City Gates in Tozeur on which one of al-Shabbi’s lines is written.

Al-Shabbi’s poetry first appeared in print in Apollo magazine, an Egyptian literary review produced by Ahmad Zaki Abu Shadi. Through Apollo, al-Shabbi’s poetry became popular across the Arab World. From 1933 onwards, al-Shabbi began collecting poetry for a Diwan, a collected works. The Diwan did not appear until well after al-Shabbi’s death. Across the subsequent three editions, there are several discrepancies, including most notably different numbers of poems, suggesting that there is some disagreement over which poems by al-Shabbi ought to be allowed to circulate. Some poems were written and rewritten over time, whilst others were never ‘finished’ and others simply do not match the poetic and artistic qualities of the poet’s other works.

One of the most notable features of al-Shabbi’s poetry is the despecification of time, place and women. His poetry appears to operate outside of time and space, in a world all of its own. The beloved is but an archetype, an image of woman. His poetry has therefore been able to transcend his circumstances and speak to a universality of experience. When al-Shabbi talks of a new day (in, for example, his landmark poem 'al-Sabah al-Jadid’ which means the new day), it is not insistently tied to the freedom that awaits the subjugated people of colonial Tunisia: it can be a new day for all who seek hope.

Al-Shabbi’s poems have been put to music by Tunisian, Egyptian and Lebanese composers, and was issued in 5 CDs. You can listen to one such song here. Across Tunisia, al-Shabbi continues to be memorialised. His mausoleum in Tozeur is open to visitors, where one can also stroll around al-Shabbi Gardens. Just outside of Tozeur, there is a statue of al-Shabbi carved into the rock face, and, emblazoned on the city gates, one can read one of his most famous lines. You can view the slides of my lecture “The National Poet as an Oriental Carpet” here.

Mohamed Sghaier Awlad Ahmad (1955-2016)

Awlad Ahmad was, arguably, for Tunisian postcolonial poetry what al-Shabbi was for the colonial one. For me, his work as well as his life represent a condensed summary of the creativity and the struggles of what he himself called “the other Tunisia”. I wrote the first ever essay on him in English, interviewed him and translated some of his work.

On Awlad Ahmad, I have written extensively, in particular for my article “A Revolution of Dignity and Poetry” for boundary 2. I have also written the preface to Mohammed Sgaier Awlad Ahmad: Diario della rivoluzione, ed. Costanza Ferrini, which is in Italian. With Costanza Ferrini, a big fan of Awlad Ahmed, we recorded an-hour long multlingual tribute to him after his death, in which you can hear him and several others read his poetry; this can be listened to below.

Awlad Ahmad was born in 1955 just one year before Tunisia’s independence in the small town Sidi Bouzid, a city in central Tunisia, which later became central to the Tunisian Revolution. Awlad Ahmad then moved to Tunis for his university education where he became acquainted with Leftist political groups and ideas, the Tunisian student movement and the literary scene. It was only after completing his degree at the age of 25 that he became a poet, somewhat by accident. Before even beginning to write poetry, Awlad Ahmad had had a successful career as a newspaper columnist.

After the events of 1984, the Tunisian Bread Riots, in which, because of an IMF-inflicted austerity programme, rebellions erupted across the country because the price of bread rose to levels that most Tunisians could no longer afford, Awlad Ahmad penned the famous “Hymn of the Six Days”. This poem caused his arrest and short imprisonment. The riots considerably weakened the Bourguiba administration and, three years later, Ben Ali took control of the Tunisian regime, deposing Bourguiba in a bloodless coup. At the beginning of Ben Ali’s regime, Awlad Ahmad had acquired some limited trust from the government, and thereby managed to found the Bayt al-Shi’r, the House of Poetry, a unique institution in the Arab World at the time.

His initial support for and acquiescence to the Ben Ali regime was part of a wider, short-lived wave of support for the regime. As the regime became increasingly repressive, Awlad Ahmad found himself more and more marginalised, shut out from the public cultural space. He later described Ben Ali’s time in power as an era of “constitutional waste and democratic lies”.

More so than many Arab poets and artists, whose works and ideas reference pan-Arab or global concerns, Awlad Ahmad is a uniquely local, Tunisian poet. His poems are suffused with a distinctly Tunisian character, references which pertain specifically to the country and its people, rather than trying to transcend his time and place as al-Shabbi had done. Indeed, Awlad Ahmad is conscious of this, often calling himself Tunisia’s national poet, even despite government suppression. The 2011 Revolution was, naturally, understood by him to be a vindication of his long-term support for Tunisian resistance. In an open letter, he wrote “The Tunisian Revolution has demonstrated that all my writings, from 1984 until today, have been right in mocking the rule of one man and of one party. . . . They are writings, which will continue in the same pace if in future a minister or a head of government wanted to play the role of a vertical god on this horizontal land.”

Awlad Ahmad’s poetry is also unusual in its adoption of the Darwishian “narrative hybridity”, its mixing of the lyric with the epic, its insistent narration. This aesthetic and ideological act, the suffusing of the poetic with the narrative, infuses the poetry with human spirit and potency. His poetry is a committed poetry, committed to Tunisia’s here-and-now, the life of the everyday, the everyman: its use of narrative then allows Awlad Ahmad to situate his poetry, to make it specific to his concerns and the concerns of the country at large. But he is also committed to rhythm and originality in poetry, meaning that his poetry is easy to memorise and perform.

Awlad Ahmad wrote poetry that was intended for performance, poetry suffused with an orality and performability that made him an eminently popular poet, whose refrains lingered in the public’s head and whose poetry appeared to give voice to a nation’s thought. His poetry is clearly an oral composition. It is easily memorable for even the least educated because it begins at the level of orality, not at the “high” register or the intensely literary. Based on repetition, rhyme, rhythm and formulae, his poetry is successful in part because it is not formulaic. It is inventive and innovative, but remains based in the patterns of a rhythmic speech.

Despite his popularity across Tunisian society, one group who has long had a fractious relationship with him are the Islamists. Most famously, he was accused of heresy by the Egyptian al-Shaykh al-Qaradawi. Awlad Ahmad wrote the poem “Prayers” in response, mixing liturgical and sacred texts and rhythms into his poetry to rebut such accusations and mock his accusers. Post revolution, Awlad Ahmad has also drawn the ire of the al-Nahda (Ennahda) Party, the Islamists that were originally thrust into a position of power after the Revolution, but that has received less and less support in the intervening years. For Awlad Ahmad, however, the Islamist cause was inherently unable to fulfill the ideals of the Revolution, and, he feared would only serve to hijack the revolutionary spirit.

Sadly, only five years after the Revolution, Awlad Ahmad died of cancer. I translated the text of his last major appearance, his “Speech in Tribute” to the Tunisian people. I also was lucky enough to meet with him before his death and record the interview below.